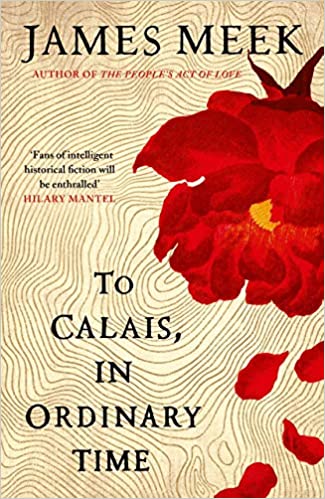

Book Review: TO CALAIS, IN ORDINARY TIME by James Meek. Canongate Books, 2020.

Read & reviewed by Jane Mack, February 2022.

TO CALAIS, IN ORDINARY TIME takes place in England starting on July 6, 1348. Medieval feudalism sets the foundation of relationships. Catholicism colors daily life. Persistent war with France lurks at the periphery. Rumors and reports of plague blow on the wind with the same perverse irregularity as the weather.

The Opening

In Outen Green, Sir Guy Corbet plans to marry off his daughter, Lady Bernadine (Berna), to an old widower with a daughter, whom Sir Guy then intends to marry himself. Lady Bernadine decries the plan to her cousin, Pogge, and clings to romantic love for Captain Laurence Haket, a military man whose proposal was rejected by Sir Guy. The theft of Berna’s wedding dress delays the marriage, but a new date is set upon receipt of an exact duplicate dress made at Sir Guy’s behest. Rather than endure the misfortune of lost love and an odious compelled marriage, Berna flees on her horse, wearing the wedding dress and with very little other preparation.

Complications

Hayne Atenoke is a giant of a man, from Gloucestershire. He requires a score of archers to go to Calais with Captain Haket to serve Lord Berkeley and the King in the continuing war with France, started in 1337. Sir Guy must provide one bowman as his feudal obligation. He selects the young ploughman, Will Quate.

Will Quate is bound to his lord as a feudal “villain” (serf), and says he may not leave as his work is to plough the fields; Sir Guy offers him freedom. Will Quate, who cannot read, wants it in writing. Sir Guy prepares the documents that empower Captain Haket to free Will upon his faithful service in Calais.

Captain Haket, having lost out on the marriage of Berna, consoled himself with a tryst with the pretty village girl Ness Muchbrook, and left before he realized she was pregnant. He does not rescue Berna or ravish her as the lover did in Romance of the Rose, a novel Berna read with him.

Ness Muchbrook, betrothed to Will, went away briefly and returned without child. She begs Will not to go with the bowmen. Will Quate shall go upon his honor.

Hab, the pigboy, insists that Will loves him, not Ness Muchbrook, and demands an acknowledgement. Will denies him.

The Thread of Reason

Thomas Pitkeno, born in Scotland, educated in Avignon, is on assignment as a proctor at Malmesbury. The abbot and the prior engage in a tug of war over control, and it is Thomas who is assigned to go with the archers to hear their confessions in the event they face death. Thomas demurs. He has heard that plague spreads throughout Europe and expects it will reach England; he prefers to stay safely tucked away in the abbey in Malmesbury, but he cannot avoid the assignment to travel with the archers to Calais.

What is a score?

The score (meaning twenty) of archers is actually only a handful, with an expectation that others will join on the road south to the waiting ship that will take them to Calais. One named Noster leaves at Outen Green, and warns Will Quate that they are a bad lot. Will, assured that Hayne is on the side of right, says he’ll go with them.

As the story progresses we meet the other bowmen, Madog ap Ithel, (Mad) a Welsh bowman with a talent for creating ballads, Gilbert Bisley (Longfreke) whose head was cleaved in two and healed with a huge scar down his face; John Fletcher (Softly) who raped the French stonemason’s daughter and took her captive, and also Walt Newent (Hornstrake), Sweetmouth, Dickle Dene, and Holiday Bobber. They fought together at Crécy under Hayne and Captain Haket. The French maiden, Cess, travels with them, and remains Softly’s captive.

The Wedding Gown

Hab dresses in the stolen wedding dress, pretends to be a maiden sister of Hab named Madlen, and appears to Will as he’s leaving Outen Green. Will refuses again to express love for Hab and refuses to believe that Hab is a maiden unless he can touch her breast. Hab as Madlen protests such action and insists she is a fair maiden to be courted properly.

Later, when Will encounters Berna on the road with a horse, wearing her wedding dress, he assumes it is Hab. Will berates Berna, thinking she is Hab for not only stealing the wedding dress, and leaving behind his duties watching Enker the pig, but now for stealing a horse. He approaches Berna, thinking she is Hab in disguise, and reaches into her dress to touch her breast. He’s shocked at the feel of her, but not as much as she is shocked by him.

“Is this what happens when we leave the places we were born?” (Berna) demanded of her horse. “That a noble lady is deprived of her authority, and a villain transformed from an obedient servant into a savage, senseless beast?”

When Berna herself meets Hab, he tells her that he is searching for his sister, Madlen. Berna, like Will, knows of no such sister and refuses to believe Hab. Hab, eager to follow Will to Calais, proposes that he follow Berna for her protection. He concocts a plan where others will treat her as a Lady, but Will Quate will not betray her to her kinsmen because he will assume she really is Madlen, sister to Hab. Berna laughs, and likes the idea of Berna pretending to be the fictional Madlen pretending to be Berna.

On the Journey

As they fall in together, the bowmen with their new archer Will Quate, the Lady Bernadine pretending to be Madlen with Hab, who eventually runs away and returns as Madlen, acting the maid to Berna, and Thomas the proctor, the road and journey evolves for each.

Thomas, who is sure the “qualm” is going to kill him, seeks forgiveness for each of his sins in the missives he writes.

∙For him “each stratum of confession, once removed, reveals another.”

∙For Berna, acting out the Romance of the Rose, upon finding Laurence Haket had sex with Ness Muchbrook, reels from the betrayal and abandonment, but clings to the novel’s promise: ““Hope is your salvation,” says Love.”

∙For Will, the discovery of genuine love for Hab/Madlen provides solace as he faces the challenges of his company of bowmen.

∙For the bowmen, the past casts a long shadow on everything they do, and the presence of Cess the captive keeps alive their greatest sins.

What I Liked-Language

The characters are compelling and the story time and place wrap themselves around the reader, creating a complete picture of a different world. The language is rendered using archaic terms and an old style grammar, where “stint” means stopped and “ne” is a general negative like no or not, don’t or didn’t. For the people of the Cotswold like Will, Hab/Madlen and the bowmen, the language is even more dense or remote. Lady Berna expresses our frustration when she doesn’t understand it, either.

“It’s Cotswold,” said Berna. “It’s Outen Green. As if no French never touched their tongues. I ne know myself sometimes what they mean. They say steven in place of voice, and shrift and housel for confession and absolution, and bead for prayer…”

Period Detail

The vocations and activities of the people in this world are medieval, with a hayward (in charge of the fence and hedge around the town common), a bow master (who teaches all the young men archery), a warrener (tending to warrens of rabbits, an imported species to England), a reeve (who oversees discharge of feudal obligations) and of course millers and smiths.

Other details also bring the setting to life. The transportation is generally on foot, with the occasional horse or cart. The medical thinking focuses on humors, bad air, and hot and cold. The plumbing usually consists of a chamber pot and a pitcher of water. James Meek, the author, richly embroiders daily living, including the stench, the inconvenience, the dirt, the discomfort, the manner of eating and even the description of sexual encounters with the period language and detail that evokes a full experience.

The Qualm

There’s plenty of plague lore in the story, also. If you’re familiar with other plague literature, it will seem familiar. If you’re only familiar with modern experience with a recent pandemic, it will still seem familiar. There are rumors that the plague isn’t a real threat and only a scam or con by the church to raise money; or if it is real, it’s a man-made action against the church; or passed along by witches. Some express beliefs in faith to heal or protect. There is the story of the person taken for dead who was really alive. Some never sicken and some recover. There are those who suffer great pain. There are protections from amulets, to blindfolds, to instructions about the wind.

As the group of travelers head further south, the plague “qualm” becomes more real, more tangible, more visible. Eventually whole villages are empty. The cows are crying because they need to be milked. There’s more food than people to eat it.

Universal questions

The questions the archers, Berna and Haket, Hab/Madlen and the proctor all face concern their mortality and immortality, and most essentially, their identity. The theme of identity is woven inextricably throughout the story, with characters pretending to be others, with them taking on roles in a play on the road, with examination of their past lives, with exploration of their commitments and with truth in the face of imminent death. Cecile du Goincourt announces her name proudly and rids herself of all that tied her to her captor. Lady Bernadine adopts her dead husband’s identity for protection. Madlen departs and Hab re-emergences. Will Quate ends with the statement:

“Death ne needed me,” said Will, “and now I ne know who I am.”

He was on his way to Calais as a bowman, to fight as a soldier, for Captain Haket. On the way, he won his freedom and found love. At the end, though, his identity, that which seemed the most solid and reliable throughout the story, is suddenly uncertain. It is this last sentence that seems so unsettling, but which seals the theme of identity in the story.

What would have made it better

A map! For those of us not familiar with England, a map would have been at treasure.

A glossary would have helped, also.

Conclusion

I truly enjoyed reading this novel. I highly recommend it, especially if you enjoy entering another world or appreciate historical fiction. The last sentence is hard to take. Without it, however, I might not have recognized how identity drives the story. I think this is the kind of novel that I will read again, better informed and more aware on the next go-round.